Two Birds with One Blockade

Cuba in the Trump-Maduro crisis

As many of you are now no doubt aware, the United States is currently blockading the coast of Venezuela. An actual blockade, not just a rhetorical device to describe economic sanctions. There are at least 8 active military vessels operating off of the Venezuelan coast in December, including aircraft carriers, destroyers, and troop landers, representing a massive escalation of the Venezuela-US relationship and Venezuelan political crisis of recent years.

This post is not to say what will happen next here. I genuinely have no idea if Trump will stay true to his name and TACO (Trump Always Chickens Out) or if we are on the verge of an actual US military intervention in Venezuela itself. I am not entirely sure if Trump’s own White House knows, especially since regime change via military intervention goes against the desires of the isolationist wing of his coalition as well as - it seems - the president’s own desire to avoid another extended military quagmire abroad. Unlike murdering people on speedboats in the Caribbean without trial or due process, some of whom may have been drug dealers or in organized crime but we will likely never know now, the current naval blockade of Venezuela now includes a new policy which will bite Maduro in the pocketbook; the seizure of oil tankers. One oil tanker has already been unilaterally seized by the United States military and, given the risks involved, it is unclear how many ships will continue to service Venezuela’s export trade.

Venezuela is still a petrostate, something that has intensified under Chavismo as industry and agriculture withered, and one constantly struggling to keep its bills paid and its army happy, so this is no longer just saber rattling. According to Bloomberg, Venezuela currently has about 10 days of oil production capacity more in its storage facilities before it has the huge problem of having oil but nowhere to put it. Without the ability to export oil, and thus pay for anything, Trump has Maduro por los cojones (by the balls). While slightly less obvious, second set of cojones in Trump’s hands are those of Cuba.

The energy problems of Cuba are not new, by any means, but in the past half decade the electrical grid has entered into its worst crisis in decades or even in the whole of its history. Already in sharp decline due to the economic crisis in Venezuela, Venezuelan oil has also been severely curtailed in recent years as daily production of oil (measured in barrels) has fallen off a cliff from the country’s peak years over the previous two decades. Adding to the death knell of Cuba’s oil reexport economic model, where part of the oil went to consumption but much of it was refined and reexported for hard currency during the oil boom, is the issue that now there isn’t enough oil to keep the island’s powerplants humming at maximum capacity. Even worse, the same powerplants are also increasingly obsolete, losing 25% of their maximum energy generation capacity in the past 5 years.

Cuba also depends more and more on its own oil production, which is not only well below the island’s energy needs but is also ‘heavy’ with contaminants which require significant refining before use. It seems that whether for practical reasons, like time, or economic ones, such as hard currency to buy key refining inputs, Cuba is increasingly using whatever oil it has without refining it enough. This is suggested by the complaints about sulfur buildup amid the now chronic problems of power plant fires and short-outs caused by the buildup of sulfur (which should have been refined out). The country is, thankfully, no longer suffering from days long national blackouts, but the ever tightening energy rationing measures by the state must feel like de facto national blackouts for citizens. Over half the country is regularly without energy during peak hours and citizens in the provinces suffer from blackouts of upwards of 20-22 hours a day. In this regard, Cuba’s energy crisis is still worsening from when I was there in 2024, with no sign of improving any time soon.

In this context, cutting off Venezuelan oil exports is going to be a gut punch for Cuba. It is unclear how much oil reserves Cuba has, but if the constant blackouts are any sign it isn’t much. Mexico can presumably step up a little, but Cuba support has its limits as Mexico’s own oil sector suffers from major problems, its best years long behind it. Russia seems a more likely candidate for help, but the enormous and generously priced oil supply during the USSR days is long since over and with the Ukraine War increasingly biting into the Russian economy it seems like the country isn’t well placed to play sugar daddy even if it wanted to, which it also does not. China has the nigh bottomless pockets and, on paper at least, ideological affinity that might justify becoming the next sugar daddy providing Cuba with cheap oil, but so far it seems to lack interest in helping more than it already is.

Venezuela’s relationship with China is also not exactly going to inspire much hope in Havana. While China is vocally supportive of the Maduro regime, it also refuses to get involved directly in stopping Trump or providing the kind of surge in military and economic aid that might help the Chavista dictator stay in power.

That Cuba’s cojones are in a vice is not incidental either. While it would have probably been sufficient to infer that this was part of the intent behind right wing Cuban American Senator-cum-Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s strategy, the NYT just published a piece confirming as much.

Although I have seen some trying to reduce Trump’s Venezuela policy to just being about Cuba, I also think that this is a mistake. Cuba is obviously part of the equation, but Venezuela policy also has obvious buy-in for different factions in his government on other grounds too. Just to list a few, there’s Venezuela as a way to keep China out of the hemisphere, Venezuela as a major source of outmigration under Maduro, and Venezuela’s role in drugs. It should be noted that on this last point Trump is certainly a massive hypocrite and his talking points on Venezuela are definitely a gross misunderstanding and exaggeration of the facts, it is also true that the Maduro regime has had relationships with drug dealers for years. Hell, Maduro’s own in-laws, his wife’s nephews, were arrested in Panama some years back on drug charges, leading to the fitting nickname for them of the narcosobrinos (narconephews). To quote a recent NYT piece on this,

The 28-page indictment says Mr. Maduro, a former bus driver and transit union leader, came to lead a drug trafficking organization, the Cartel de Los Soles, or Cartel of the Suns.

Experts say the Cartel de los Soles is not a criminal group in the conventional sense, but shorthand for a patronage system in which military and political elites profit from drug smuggling and other illicit trades. Its name refers to the sun-shaped insignia on the uniforms of high-ranking Venezuelan military officials, the indictment notes.

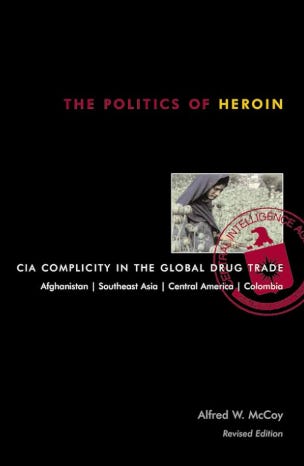

Basically, the regime is complicit in drugs, it is not itself a drug cartel. Both during the Cold War and since, both the US and various regimes opposed to it have adopted the use of drugs to finance conflict. One of my Professors at UW-Madison, Al McCoy, has dedicated a large part of his academic career to studying this very issue around the world, and at this point the complicity of every band of the political spectrum in drugs at some point is an established part of the historical record.

It is clear, however, that no one of these issues is the simple straightforward explanation for Venezuela policy, much less in the ways in which these factors are invoked publicly. The case of Guatemala in 1954 also gives me some pause to dismiss all of Trump’s more absurd claims. When the CIA overthrew democratically elected President of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz, it did so seemingly in the sincere belief that he was leading the country towards communism. While the harmed interests of the United Fruit Company was certainly part of the domestic pressure factors that led Eisenhower to greenlight the 1954 coup, as time has gone on and access to archival records expanded it increasingly seems like the problem was that anti-Communist paranoia managed to convince the Eisenhower administration that Arbenz was somehow a Communist. With this in mind, I am still wary of coming down too hard on a specific explanation for why the Venezuela crisis is reaching the heights that it is, not just yet anyway.

What does seem more certain is that Cuba is in a bind right now. If oil supplies were already bringing the economy to its knees, this will make it somehow even worse. Over the mid-to-long term I can see Cuba figuring out some kind of alternative, maybe, depending on how generous other suppliers or potential sugar daddies feel, but short-term this seems on track (short of other countries stepping in quickly) to put a hurt on the island’s economy at a time when the patient is almost bedridden already. That, of course, is part of the idea; Cuba is on life support and some in Trump’s administration want to see what happens if they pull the Venezuelan plug.

Thanks

Do you have any clue about solar capacity in recent years? In january, a guy from a Casa Particular (he was clearly a bit aligned with the government) in Trinidad (where electricity was rationed) said that the situation would get better in a couple of weeks with some solar parks.

This relates to my second question, can China’s support be much more on channelling solar “overcapacity” to the island instead of oil tanker? Pakistan solar expansion in a period of crisis has been quite impressive.

https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/pakistans-solar-surge-lifts-it-into-rarefied-25-club-2025-06-17/