"Factually Based"

A response to Leslie Feinberg’s claims about Cuba’s UMAP labor camp system

Please stop citing Leslie Feinberg’s book, Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba. More specifically, please stop citing its section on the UMAP and why they were closed down. The entire purpose of writing this piece and tracking down all the sources, critically comparing them, and pointing out problems, is to hopefully convince good faith people to stop sharing it.

This piece has been in the works since at least 2019 and I have been coming across some of the misinformation that it spreads for several years even before that. Although, at the time, I did not know it was she who had helped popularize them to an English-speaking audience.

In what follows I have done my best to steelman my response to the problems with Feinberg’s research and arguments. This means I will be engaging with it on its own terms and will try, where possible to offer the most sympathetic and strongest interpretation of Feinberg’s points that I can think of. As I’ll discuss at the end of the piece, even after doing all this work I do not think that Feinberg necessarily did any of this maliciously. Understanding Feinberg on her own terms, however, does not excuse her from the consequences of spreading these myths. Especially when it comes to something as serious as the abuses done to LGBT people in Cuba, where the work camps she tries to minimize are still an open wound for many.

What the hell is an ‘UMAP’?

Starting around 1965 and ending around 1968, the Cuban government created a series of labor camps in the province of Camagüey, in Central Cuba. They were called Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción (UMAP), meaning Military Units to Aid Production. As the name suggests, they were run by the military and had the purpose of using the labor of those sent there in ways that contributed to the state sector economy. While the camps are most infamous for interning gay men, many were also sent there for other reasons, from Jehova’s Witnesses to hippies to people who just more broadly were seen as having ‘inappropriate conduct’. The exact number of detainees sent to these camps is unclear, because the Cuban government has still not declassified and made relevant records public. Typically estimates for those sent to the UMAP range in in the thousands or tens of thousands.

Among those sent to the camps was the renowned singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés, who was interned there from 1965-1967. According to Milanés, he was one of thousands of youths sent to the UMAP, which he refers to as “concentration camps”, for the crime of being freethinkers and having opinions.[1] While he was not sent to the camps for being perceived as gay, he saw many who were, and recounts in one interview how they were treated notably worse than even the rest of the internees, who were themselves also mistreated. He claims that even within the camps, gay men were ghettoized and isolated from the rest of the internees.[2]

This was happening in the midst of a broader offensive against gay men in Cuba. We can see evidence of this in articles in official publications, like the state approved magazine Mella, which published a May 31st, 1965, article calling for the expulsion of “counterrevolutionary and homosexual elements” in the final years of their high school education, so as to prevent their getting into the university system. Homosexuality, or at least transgressions against contemporary social norms about how men should act, was conflated with being “petty bourgeois” and opposition to the new revolutionary government.[3] In the University of Havana’s official student newspaper, also published with approval by the state, an article was published soon after that claimed that “neither elements disaffected with the Revolution nor homosexuals are capable of fulfilling” the expectations of revolutionary young people, “therefore the product of the sweat and blood of our people should not be invested in them such that they can turn against society.”[4] In her book Visions of Power in Cuba, historian Lillian Guerra dedicates a whole chapter to how part of the project of constructing a revolutionary youth was connected with the imposition of strong heteronormative expectations on youth, and especially on male behavior.[5] An especially explicit defense of anti-LGBT policies during this period was given by pro-revolution Cuban writer Samuel Feijóo in April 15th, 1965, issue of the newspaper El Mundo. In a piece called “Revolución y vicio” (Revolution and Vice) that “it is not about persecuting homosexuals, but instead destroying their positions, their procedures, their influence. That is what is called revolutionary social hygiene.”[6]

Nor was this limited to words. While publications printed calls for purges of gays and lesbians from higher education, the Communist Youth (Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas or UJC) and the by then state controlled student union (Fedecación de Estudiantes Universitarios or FEU) were actively engaged in a years long purge of higher education. They would hold public trials of students, called depuraciones (literally “purges”) and distribute homophobic literature warning against association with “the little sick ones”, as they referred to LGBT students. Campus audio systems would regularly sound out announcements of new purges where juries made up of UJC and FEU affiliated students. These would publicly denounce specific students of being LGBT and call witnesses against them. Students would then be expelled from the universities as a result of these kangaroo courts and the fact that they were expelled for being LGBT would be added to their official worker files, which would follow them for the rest of their working lives. The head of the UJC even proposed expanding the practice to high schools and secondary schools.[7] Throughout this process, homosexuality – seen not as an inherent preference but as a sort of ideological distortion – was seen as comorbid with “intellectualism”, Trotskyism, and slightly more bizarrely “reunionism” (the tendency to hold too many meetings).[8] In short, the UMAP were not an isolated policy, but part of this broader societal push against LGBT Cubans.

Example of a homophobic cartoon, conflating homosexuality with being bourgeois, unmanly, and out of step with the Revolution. From the magazine Mella, May 1965 edition. Reproduced from Lillian Guerra’s Visions of Power in Cuba.[9]

Between testimony and written records, there is a convincing case that the camps were meant not merely to isolate and extract the labor of LGBT Cubans, but also to modify their behavior to be more heteronormative. As Lillian Guerra describes in her book Visions of Power in Cuba, in 1965 the Ministry of Public health argued that homosexuals exhibited a natural vulnerability to imperialist propaganda. “Homosexualism,” spoken of as a sort of ideology, was thought of as a potential result of “intellectualism”. “Productive labor” in agriculture was a key tool in modifying behaviors the Cuban state saw as negative and aberrant.[10] Nor was this exclusively used against LGBT Cubans. Guerra also discusses how former sex workers who refused to leave sex work behind were also sent to forced labor in agriculture as part of the state’s project attempts to do what it perceived as rehabilitation.[11]

Eventually, the camps were closed. The explanations for this vary. In a piece he wrote in the midst of the Padilla Affair in 1971, the Cuban American journalist José Yglesias (a former film critic for Communist Party USA’s newspaper The Daily Worker)[12] mentions that that the UMAP were closed because of opposition from the cultural world. In his telling, the Union of Writers and Artists (UNEAC in Spanish), the state sponsored writers and artists labor union, had an emergency session after five prominent artists were told to report to the UMAP, “presumably because they were homosexuals.” The session supposedly demanded, unanimously, that the order be rescinded while members also flatly condemned the UMAP. “It was then that Fidel promised that the UMAP would be dissolved, and he and others, I was told, personally, apologized to the five artists.” This all seems to have happened around 1966,[13] though Pablo Milanés was supposedly interned as late as 1967 and the standard dates for the UMAP have it going until 1968. In another telling, the former revolutionary turned opposition figure Carlos Franqui claims to have vocally opposed the UMAP’s internment and abuse of gay Cubans. Supposedly he and two Italian friends, who were all working on a book on Fidel, met with the Cuban leader personally. The discussion was the topic was extremely heated and tense, in Franqui’s telling. Fidel allegedly defended the persecution of gay men by saying that the revolution needed strong young men for its army, men who also couldn’t be blackmailed about their personal lives. While Fidel, according to Franqui, believed that gay men were a bad example for the army, he also recognized that they had also been physically abused in the UMAP. As a consequence, Fidel allegedly promised to close the camps after their discussion.[14] According to singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés, the camps were dissolved as a result of the international scandal that resulted when news of them came out, meaning that the key factor in that version is international pressure.[15] It is possible that some or even all of these versions are at least partly true, though each version also tends to be presented as the single cause of the closure of the camps. It is also possible that Fidel just kept telling individuals, on a private level, that he planned to close the camps and then kept leaving them open anyway, acting each time as if he was only just hearing about the abuse. Whatever the truth, none of these are the versions included in Feinberg’s book.

Due to extremely limited archival access, not a lot of in-depth work has been done on the UMAP. Lots of articles and blog posts exist, as well as some theses and dissertations, and more recently a long book by the academic Abel Sierra Madero, in what is probably the most extensive treatment of the topic to date.[16] The most influential source on the UMAP, however, is probably still the 1980s documentary Conducta impropia (Inappropriate Conduct), made in the wake of the Mariel Crisis in 1980. In it, former internees of the camps as well as exiled political figures and intellectuals are all interviewed about their experiences.[17] While some progress has been made documenting the UMAP, given that it was a military program, that even many surviving political figures would be implicated, and in particular that Raúl Castro was personally in charge of the military at the time, it seems unlikely that we will have fuller access to records connected to the UMAP anytime soon. Due to the lack of transparency or restitution to victims, it will come as no surprise that the UMAP are still a sort of open wound in Cuba.

How is the legacy of the UMAP discussed by the Cuban state?

From the 1990s onwards, Cuba has thankfully taken a steadily more progressive stance on LGBT issues. As imperfect and uneven as this progress has been, we are potentially about to see yet another important step forward if the referendum to legalize same-sex marriage is approved later this month. However, even the spearhead of these efforts within the Cuban government, Mariela Castro, the head of the Cuban National Center for Sex Education (CENESEX) and Raúl Castro’s daughter, has recognized the need for further investigations into the abuses against gay men in the UMAP.[18] During his later years, Fidel Castro finally began to shift his rhetoric to acknowledge abuses of LGBT people during his time in power. It is worth noting, however, that despite claims that he accepted responsibility for these abuses, he only acknowledged ultimate responsibility, as the one in charge of the country, which is different from taking substantive responsibility in this case. He acknowledges that there were abuses, but distances himself from any personal homophobia on his part or from any specific role in the UMAP themselves.[19]

Only a few years before this shift, he discussed the issue very differently in the book Cien Horas con Fidel (One Hundred Hours with Fidel), a series of interviews conducted by Spanish journalist Ignacio Ramonet. In it, Fidel insisted that “there was never a persecution of homosexuals, nor camps for interning homosexuals.” When pressed by Ramonet, who said “but there are many testimonies about that”, Fidel responds by contextualizing what happened to gay men as part of the need to “mobilize almost the whole of the countries” in the context of the Cold War and need to respond to foreign aggression. As a result of this pressure, “obligatory military service was created.” Some young men who were of age to be taken into the army were not able to be incorporated into the military normally; those with insufficient education, those who refused military service due to religious convictions, and “the third case, that of the homosexuals.” Based on these categories, the UMAP were created. In the interview Fidel claimed that, initially at least, the policy was not to induct gay men into the army at all, due to machismo in the ranks, but that over time this caused even more anger to be directed at gay men due to their de facto exemption from service. However, Fidel insists throughout that they were not “internment camps, nor punishment units [note from the author: this will be relevant towards the end], but instead attempts to elevate their morale, give them the possibility to work, to help the country in those difficult circumstances.” In short, per Fidel Castro the UMAP were a sort of alternative military service focused on economic tasks over military ones.[20] However, of course, Fidel would reverse himself only a few years after the publication of this book in the mid-aughts and accept the fact of persecution of gay men in Cuba to the Mexican journalist Carmen Lira in her interview of him for Mexico’s La Jornada, where the interview focuses on how gay men were “persecuted”.[21] The key point here is Fidel’s framing of the UMAP as a sort of benign alternative to standard military service that were entirely above board. This is the framing that Feinberg would go on to use in her book, citing Ramonet, published was before the Carmen Lira interview in 2010.

In terms of broader historical narratives about the treatment of LGBT Cubans after 1959, the UMAP are still pointed to as one of the bleakest and most shameful of policies ever enacted by the Cuban Revolution. They preceded the anti-LGBT policies of the 1970s, when another systematic attempt was made to purge culture and education of gay influences, as well as gay men in positions of influence or power generally. The best-known part of this campaign was the purge of LGBT artists and writers from any position in which they could produce their art during the five years between 1971 and 1976, often referred to as the Quinquenio Gris (the Grey Quinquennial). On a broader societal level this also included policies meant to prevent gay men from becoming teachers,[22] which like culture was seen as a way that LGBT people could influence and corrupt the youth. While things weren’t especially great in the 1980s, policies improved intermittently during the 1990s and early 2000s, and have made even bigger strides since. Although the Cuban state’s model of trying to push LGBT activism into only specific official channels, like CENESEX, in a model similar to how women’s rights and feminist causes were to be channeled specifically through the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC in Spanish), it is hard to deny that positive policy changes have occurred over the past several decades.

While the legalization of same-sex marriage was originally going to be part of the new constitution in 2019, it was separated from the referendum on the broader constitution due to popular pushback even within the government’s own coalition as well as the organized opposition of the religious right. Hopefully, if the upcoming referendum passes, in a few weeks we can finally celebrate the important milestone of same-sex unions as yet another major step forward for LGBT rights in Cuba.

Who is Leslie Feinberg and what was her book ‘Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba’?

Leslie Feinberg was a trans activist, writer, and self-identified revolutionary communist who passed away in 2014. She joined a Communist party called the World Worker’s Party, a Marcyite sect, in her early 20s. Between 2004 and 2008 she contributed many articles to the party’s official newspaper, Workers World, as part of its larger series on LGBT issues, called Lavender & Red. Her book Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba is an edited volume that collects the articles specifically relevant to LGBT issues in Cuba. Feinberg accepted any pronouns as long as they were used with respect, including she/her.[23] I will use one set of pronouns just for the sake of clarity in this piece.

Her contributions to the Lavender & Red series were meant as a refutation of the argument “that life under capitalism might be a hard road for [LGBT people] but that socialism is inherently worse.”[24] While she insists in her introduction to the book that her work is “factually based,” she also warns that “you will find no condemnation of the Cuban Revolution in this book.”[25] It is not original reporting, it is not meant to be a balanced analysis, and it is not even meant to criticize the Cuban state. It is explicitly a “defense of Cuba” and its policies, as the title suggests. This fits in with the broader Marcyite position that ideologically Left governments abroad, whatever their failings, should not be publicly criticized, believing that it doing so transgresses the principle of solidarity with Socialist and Communist countries around the world.

When she gets to the UMAP, Feinberg strongly criticizes negative characterizations of the camps as follows:

One of the most terrible slanders against the Cuban Revolution […] that the workers’ state was a “penal colony,” interning gay men in “concentration camps” in 1965. That charge, which refers to the 1965 mobilization of Units to Aid Military Production (UMAP), still circulates today as good coin.[26]

Feinberg’s counternarrative is largely based on the already discussed interviews between Fidel and Ignacio Ramonet. She uncritically embraces Fidel’s argument that the UMAP were merely an alternative form of military service, which the government embraced due to the pervasiveness of homophobia in the Cuban military, which prevented their incorporation into normal military units. She also points to the economic crisis that the country was going through by the mid- to late-1960s was another core reason for the UMAP. In short, the UMAP were an outlet for the labor of gay Cuban men which could not be canalized through the normal channels of Cuba’s obligatory military service.[27]

Ironically, one of the central pieces of evidence that she cites for the banality of the camps is the fact that singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés was sent to the UMAP, but still decided to stay in Cuba and build the Revolution afterwards.[28] This is the same Pablo Milanés who would go on, only a few years later, to call the UMAP “a Stalinist measure of repression” and label them “concentration camps”. In this same 2015 interview Milanés describes escaping from one of the camps under the belief that if authorities were alerted that they would immediately shut them down. Once back in Havana he did so and was imprisoned for fleeing the UMAP by authorities, who for their part seemed perfectly aware of what the UMAP were and what they were doing to those sent there. He goes on to say that after two months imprisoned in the Cabaña fortress, in Havana, he was sent to a punishment camp even worse than the UMAP until the camps were finally dissolved.[29] Milanés is often described as living back and forth between Cuba and Spain and just this year celebrated a concert in Havana,[30] so he cannot be described as an embittered and conspiracy theory addled exile throwing stones from Miami.

Another of the problems with Feinberg’s explanation of the UMAP as above board in their general mission is that the process of sending people there was not always done openly. Nicaraguan poet and intellectual Ernesto Cardenal, a lifelong supporter of the Cuban Revolution, describes in his travel memoir En Cuba how he heard of traps being set for gay men. Beer would be distributed in places where homosexual men were known to gather and once enough had gathered the trap would be sprung, with the men caught being sent to the UMAP.[31] Admittedly, Cardenal is passing along a rumor that he heard while in Havana. The problem with dismissing his story out of hand, as we shall see in a moment, is that he is also Feinberg’s main source for her explanation of why the camps were closed. These also trace back to Cardenal sharing anonymous anecdotes during these same trips to Havana in 1970-1971. In another example from Cardenal, a university student named Gustavo Ventoso, who had been studying classical languages, was taken right off the street in broad daylight and sent to the camps for a year and a half.[32]

The next section of her book, where Feinberg makes the often-cited claims about Fidel’s role in the closure of the UMAP, is actually quite short, to the point that I have screenshotted it in its entirety:

The entirety of the section where Feinberg tries to explain the closure of the UMAP and Fidel’s alleged role in it.[33]

Beginning with a short citation from Ramonet’s interviews with Fidel where the latter acknowledged homophobic prejudice in the UMAP, she quickly moves on to discuss the closure of the camps themselves. Citing an article by another Leftist activist, Jon Hillson, Feinberg says that protests by the UNEAC prompted an investigation. She then offers two stories, both sourced to Cardenal’s already mentioned book. In the first story, Fidel personally infiltrates the camps to investigate claims of abuse and, after confirming them, because a guard began to mistreat Fidel personally, he revealed his true identity and shut down the camps. The second story was that 100 young men from the Communist Youth were sent to infiltrate the camps to investigate claims of abuse and report back. Once they did, stories of abuse were confirmed and the camps were shut down.[34] Despite the seeming contradictions in these stories being fairly obvious, Feinberg doesn’t even attempt to explain how they fit together. Why would 100 Communist Youth members be sent, in what would have been a truly massive undercover operation, if Fidel had already infiltrated the UMAP personally? Flipping the chronology, why would Fidel bother personally infiltrating a camp if 100 Communist Youth members had infiltrated the camps and documented abuses there? One deeper problem is that in both cases, the main and – as far as I can tell – sole source for either story is Ernesto Cardenal’s book. If you see these stories online in English, they almost certainly trace back to Feinberg or Hillson’s articles, which in turn cite Cardenal. If anyone finds another source for these stories, please feel free to let me know.

Digging a bit deeper, I have even more problems with this explanation. First, the problem with the camps is not merely that gay men were also being physically abused there but that LGBT Cubans were being sent to do hard labor as part of a broader push to modify their behavior through hard labor; in other words, the purpose of the camps themselves, not merely the abuses there. Second, Fidel had unlimited access to the relevant documentation, and a massive, powerful, and very effective domestic intelligence apparatus, yet he was somehow blissfully unaware of what was happening in the camps without infiltrating them? Third, and finally, in what world does it seem probable that someone as obsessed with micromanaging every aspect of policy, as Fidel famously was, would have been unaware of exactly what the UMAP were and what they were doing from the start? Camps that existed not for a few weeks or months but for years, and which received numerous domestic and international complaints during that period. It’s not that it’s impossible for this to have been the case, but it’s at best extremely unlikely and definitely a claim that would need to be proven, not just implied in passing.

Worst of all, again, these are anonymous sources sharing rumors about what happened. Even Cardenal himself – the source of both rumors – does not state them as fact, though Feinberg shares both stories uncritically. In researching for this piece, I have also come to wondered whether Feinberg ever actually ever actually bothered read Cardenal directly.

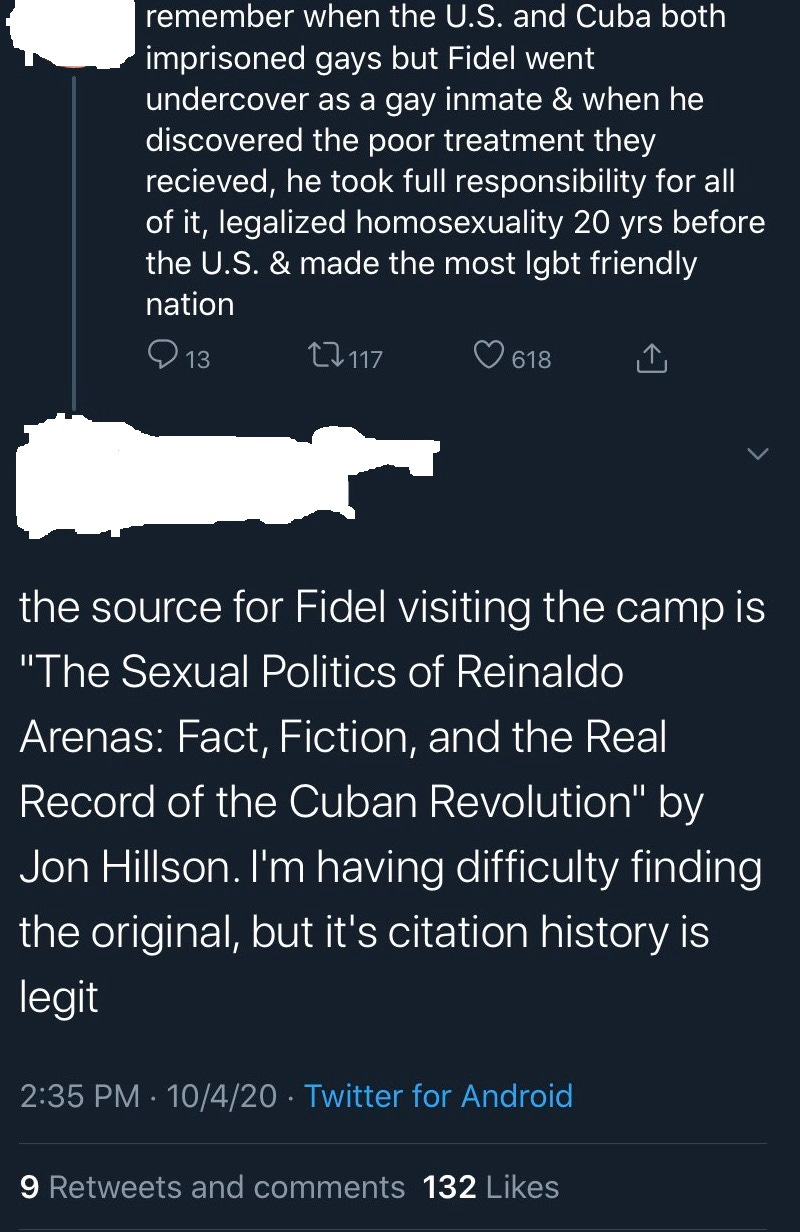

While notably less directly influential than Feinberg, Hillson’s work has been another major source of misconceptions about the UMAP. Another anonymized screenshot of a different account.

As I’ve already mentioned, Feinberg cites an article by Jon Hillson in this section after acknowledging that the sources of both stories about the UMAP’s closure are from Cardenal. Hillson was a socialist activist who did a lot of organizing around solidarity work in support of Cuba.[35] In the early 2000s he began to write about Cuba’s track record on LGBT issues in response to public discussions of the mistreatment of gay Cuban men caused by the film Before Night Falls (Dir. Julian Schnabel, 2000), a biopic about the gay Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas. Arenas had been persecuted both for being gay and for his critical stance towards the government, eventually resulting in his fleeing the country during the Mariel Boatlift in 1980. In response, Hillson penned a piece in 2001 titled Sex, Fiction, and Truth: Reinaldo Arenas and the Cuban Revolution. Several years ago, I was able to find the piece on the website of the NNOC, a Cuba solidarity organization, though it appears to have since been scrubbed from the website.[36] The only other link to any copy of the piece I could find is on another website whose link is to a domain that no longer exists.[37] It is unclear to me whether another online copy of this article exists. If you have one, please send it along so I can link to it.

The key thing here is that Hillson’s piece also cites Cardenal’s stories about Fidel and the 100 Communist Youth members who infiltrate the camps. In both cases, Hillson cites Cardenal. As we will see below, Cardenal is not only far more transparent about the limits of his knowledge of the situation, but also says things that completely contradict Feinberg’s various arguments and claims. I’m spending so much time floating the possibility that she failed to do basic due diligence because if she did read Cardenal and still used him this way, the only conclusion would be that she is being outright dishonest. This is an attempt to steelman her arguments, so I will proceed based on the more charitable reading of failed due diligence.

As already mentioned, En Cuba is a Leftist travelogue written in the early 1970s by Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal. He was a supporter of the Cuban Revolution, both then and for the remainder of his life. When asked decades later about the UMAP, Cardenal acknowledged the persecution while emphasizing that the camps were ultimately shut down by the Cuban government.[38] Cardenal’s book En Cuba, which is available in English,[39] is an interesting source on the period. While not a work of investigative journalism and while it lacks access to any sort of secret meetings where policy was decided, it also doesn’t claim to be either. It is a book version of the notes Cardenal kept during his travels, and he is quite transparent about this. He shares stories he is told fairly uncritically most of the time, but sees it as his duty to share to the outside world what he is being told by everyday Cubans. It also isn’t just a classic ‘I spent two weeks in Cuba and have nothing but nice things to say’ puff piece about Cuba, which is its own genre at this point, but instead one trying to point out the problems as well as what he saw as the positives. Basically, while it isn’t the most reliable source on its own, it can be useful if you approach it with care and use it together with other sources which help you determine which anecdotes sound credible and representative of Cuban reality at the time.

The sources in his book are mostly anonymous, but this is explicitly for their own protection:

An intellectual (revolutionary), on seeing me writing everything down in my notebook: “I suppose there’s no need to tell you this, but I’ll tell you anyway: when you write your book don’t put the names of people who have said unfavorable things, because it may do them harm.” (I write this, too, in my notebook)[40]

In the sectioned labeled The Young Poets, Cardenal describes meeting with two young Cuban poets who arrive at his hotel – seemingly uninvited – to speak with him about the situation in Cuba. Cardenal was interested in hearing what they thought, as young men who had grown up under the Revolution. One was teaching at a university and the other was in the militia and was even in uniform during the meeting. The conversation starts with the militia man sharing a short story he had written and complaining that it would not be published “because of the repression”. “Is there repression in Cuba?” Cardenal asked. They insisted that there was and that

We are revolutionaries, and there is repression. And the repression is not revolutionary. Repression, wherever it occurs, is counterrevolutionary. Although those who indulge in it call themselves revolutionaries, repression is always Batistan.[41]

They go on to explain to Cardenal that many come to Cuba and upon realizing that it still had all sorts of problems they go away disillusioned. The young poets wanted Cardenal to know that the revolution was deeply imperfect, but they were doing this so that he might be inoculated from total disillusionment and might come to a more balanced understanding that saw the good as well as all the bad.[42] It is at this point that the UMAP come up.

“You probably haven’t heard about the UMAP?” Cardenal responds that he had not. “Concentration camps,” the university instructor said. “They don’t exist now,” the militiaman added.

Fidel suppressed them. But nobody mentions them. How do I know about them? I was in one. Not as a prisoner but as a guard. Yes, a jailer. I saw the bad business, but we were just on guard. They told Fidel about what was going on. One night he broke into the camp and lay down in one of the hammocks to see what kind of treatment a prisoner gets. The prisoners slept in hammocks. They were waked with the saber whacks if they didn’t get up. The guards would cut their hammock cords. When one guard raised his saber, he found himself staring at Fidel; he almost dropped dead. In another camp he saw a guard making a prisoner walk barefoot on pieces of glass. He ordered the guard to suffer the same punishment he was giving to the other man. In another place he turned up at breakfast time. And so, he went around observing things. Afterwards he ordered punishments. They say that there was even an execution.[43]

They then go on to discuss other matters, like Fidel’s ignorance of the abuses committed in Cuba and of the pernicious problem of Stalinism, whatever guise it worked under.[44] The militiaman expressed hope that if he can just get his text to Fidel that it will be authorized for publication. They also criticize the lack of freedom of the press, because they believe that the Cuban people were by then politically mature enough to hear the news without censorship.[45]

Much later in the book, an entirely separate person, identified only as “a young Marxist revolutionary” told Cardenal:

“A hundred boys from the Communist Youth were stripped of their identity cards and all other identification and delivered to the UMAP as prisoners, to see how they would be treated. It was a highly secret operation. Not even their families knew of this plan. Afterwards the boys told what had happened. And they put an end to the UMAP.”[46]

That’s it. Those are the sources for those two stories. The Communist Youth story seems especially weak, with the young Marxist revolutionary not even claiming to have anything better than hearsay about it. It is a story he was repeating, potentially in good faith, but which is entirely separate from the story of Fidel infiltrating the camps. They were told by different people and seemingly never meant to be told one next to the other. Cardenal does not claim either to be a fact or imply that they are. They are merely two of the many anecdotes recorded in his journal.

The more interesting story to me is the Fidel infiltration one, because it is the one that tends to be cited the most. It’s a good story. Almost like a prophet from the bible, Fidel reveals himself and chides the guards for going astray, acting as a Solomonic judge against the one abusive guard. The militiaman also claims to have been a guard at the camps and a witness to the abuses that happened there, which makes it more credible than the Communist Youth story, which is entirely hearsay. Significantly, though, throughout the story militiaman doesn’t explicitly claim to have witnessed Fidel’s infiltration or its aftermath. He claims to have been a guard and seen the abuses, and then shares a series of stories about Fidel infiltrating the camp, even adding ‘they say that there was even an execution’. It’s understandable why, if you really want this story to be true, on a first reading you’d take it as a claim of him being there for most or even all of it. In truth, it isn’t actually clear that his time as a guard even coincided with the time that Fidel supposedly infiltrated the camps. Even if the guard is being sincere, the only part of this we hear him explicitly claiming to be eyewitness testimony is the abuse of prisoners at the UMAP that he saw as a guard. In short, this does not pass basic scrutiny as a source of what actually happened.

It’s significant that in both stories the narratives do agree on one key point: Fidel’s innocence. In both, the abuse of prisoners is treated as an aberration, the discovery of which leads to the closure of the camps. Given that the people sharing these stories are all supporters of the Cuban Revolution, it makes sense that they’d want to believe stories which freed the Cuban leadership from any complicity in the abuses done at the UMAP. Whether or not she actually believed these stories to be true, I don’t doubt that Feinberg was just as invested as the young men in Cardenal’s book in the hope that Cuba’s leadership was unaware of what was happening in the UMAP. However, again, the problem is not just awareness of abuses, but the purpose and nature of the camps themselves.

This is not the end of Cardenal’s relevance to Feinberg’s book. He goes on to contribute further anecdotes which contradict her claims. On at least two occasions he goes on to describe ‘social disgrace units’ that existed at the time of his travel there (1970-1971) in which gay Cubans, religious people, people who smoked marijuana, committed theft, or refused to work for any reason, were sent. One internee described his experiences to Cardenal:

Yes, we work in the quarries. We cut the marble with electric drills, we get it out in blocks, and we polish it. We also make cement walls for prefabricated houses, columns, staircases, that are later put together like jigsaw puzzles. The work is hard because it’s almost always in the sun. We work eleven hours a day, from seven to seven with a n hour off for lunch from twelve to one. After work you bathe, have supper, and you can go into town. At times there are marathons of voluntary work, so-called (but it’s not voluntary), in order to reach a goal, and then you work from seven in the morning to eleven at night. We are in this work unit instead of doing our military service, and in this unit there are no classes, only work. I have had to interrupt my studies for three years because you have to spent three years in the quarries.[47]

In short, they were the UMAP in all but name. The claim that a ‘social disgrace unit’ existed during this period is also made by an actual named source, one of the very few in Cardenal’s book: The Archbishop of Havana, Monsignor Francisco Oves. On hearing that Cardenal planned to visit the Isle of Pines, now the Isle of Youth, Oves recommended he visit the ‘social disgrace unit there’, where ‘marijuana smokers and homosexuals and other delinquents’ were sent to work in the island’s marble quarries.[48]

The reference to those who ‘refused to work’ is potentially a reference to the revival of a vagrancy law in 1970. As historian Lillia Guerra describes it, the Ley contra la vagancia “made refusal to work in agriculture or jobs assigned by the state a crime for the first time since Spanish rulers enacted similar laws in the early nineteenth century.”[49]

The survival, indeed the intensification of, forced labor during the late 1960s and early 1970s makes sense in the context of Cuba’s collapsing economy. Academic Carmelo Mesa-Lago paints an extremely bleak picture of the Cuban economy by 1972, as severe shortages on the island combined with an extraordinary growing debt to the USSR. By that year Cuba had run a whopping $1.5 billion dollar trade deficit (in early 1970s dollars!) with the Soviet Union and owed them 20 million tons of sugar, or about 3 complete harvests worth.[50] As the economic situation grew grimmer, the government increasingly relied on mass mobilizations of ‘voluntary’ labor from everyday Cubans in order both to function and try to reverse the country’s economic nosedive.[51] Another academic, Kepa Altaraz, openly asks whether the major turn to ideological incentives and New Man theory in the late 1960s was largely a result of the lack of other means with which to pay people.[52] Increasingly hairbrained schemes, mobilizing hundreds of thousands of people for little to no pay, were acts of desperation by a Cuban state that was rightly worried that the economy was going to collapse. This is the context of the work camps. Various marginalized people, whether for sexual orientation, political views, or a combination of the two, were an easy labor pool to tap in such times. It was less socially unacceptable to go after them, the country’s crisis seemed to justify extraordinary measures, the belief that forced hard labor would reform their behavior was the sweetener on top.

Conclusions

An anonymized account discussing claims about the UMAP that were popularized by activists Leslie Feinberg and Jon Hillson. It is unclear whether this is referring to either of them, or a third source.

To summarize, Feinberg’s book’s claims about the purpose, duration, and end of the UMAP do not survive basic scrutiny. However, I do not want people to come away from this piece – where I’ve been very critical of her work – thinking that I have made no attempt to understand things from Feinberg’s point of view. As an LGBT activist herself, this is doubtless an issue she cared about very much. In a sympathetic reading of the text, it is possible to see Feinberg as being taken in by stories she genuinely wanted to believe. The brain is a powerful information sorting and pattern seeking tool which is great at putting narratives in front of us that jibe with how we see the world and how we want the world to work. None of us, including me, are immune from this.

Feinberg also wasn’t wrong that many conservatives can and will continue to cynically bring up the mistreatment of LGBT people in Cuba, not because they give a damn about the people involved but because it’s a way to score points. We can see contemporary examples of the same phenomenon in right wing Miami Cubans complaining about the mistreatment of Afro-Cuban activists and protesters in Cuba, while opposing BLM protesters here at home, including working to penalize BLM protests. The cynical use of Cuban suffering by people who patently do not care about everyday Cubans, or marginalized groups in particular, and only want to use their pain in order to score political points should rightly grate people of good will anywhere. This does not, however, justify becoming complicit in covering up or minimizing crimes committed against Cubans by the Cuban state.

It’s also not as though Feinberg’s book is the finger in the dam preventing people from talking about the UMAP. If anything, Feinberg’s main audience is other Leftists who want to buy what she was selling, not Liberals or Conservatives, who will never hear of her book and who if offered it would dismiss it out of hand. To defend her book, despite all these massive problems, is an act of self-indulgence for a book that helped people feel better about a dark period in Cuban history, not an act of solidarity in support of Cuba or its people.

I can’t make people change their minds about Feinberg or stop people from sharing it. That’s up to everyone else’s conscience. One thing is for certain though: now you can’t say that you haven’t been told.

Thank you for reading.

[1] “Pablo Milanés, Cantautor Cubano: ‘En La Cuba Revolucionaria Hubo Campos de Concentración’ - La Tercera,” accessed September 1, 2022, https://www.latercera.com/cultura/noticia/pablo-milanes-cantautor-cubano-la-cuba-revolucionaria-hubo-campos-concentracion/116034/.

[2] Pablo Milanes Habla de Su Paso Por Campos de Concentración En Cuba(UMAP), 2020,

Timestamp 4:28-5:44.

[3] ABEL SIERRA MADERO, “‘El Trabajo Os Hará Hombres’: Masculinización Nacional, Trabajo Forzado y Control Social En Cuba Durante Los Años Sesenta,” Cuban Studies, no. 44 (2016): 323.

[4] MADERO, 323.

[5] Lillian Guerra, Visions of Power in Cuba: Revolution, Redemption, and Resistance, 1959-1971 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 227–55.

[6] “Academias Para Producir Machos En Cuba | Letras Libres,” accessed September 2, 2022, https://letraslibres.com/politica/academias-para-producir-machos-en-cuba/.

[7] Guerra, Visions of Power in Cuba: Revolution, Redemption, and Resistance, 1959-1971.

[8] Guerra, 248.

[9] Guerra, 250–51.

[10] Guerra, 229.

[11] Guerra, 283.

[12] “Jose Yglesias, Novelist of Revolution, Dies at 75 - The New York Times,” accessed September 1, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/08/arts/jose-yglesias-novelist-of-revolution-dies-at-75.html?pagewanted=all. Also, yes, this is Matt Yglesias’ grandfather.

[13] “The Case of Heberto Padilla | Jose Yglesias | The New York Review of Books,” accessed September 1, 2022, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1971/06/03/the-case-of-heberto-padilla/.

[14] Conducta Impropia Documental Sobre La Represion al Homosexualismo En Cuba, 2018,

Timestamps 1:15:00-1:18:50.

[15] “‘La Apertura Cubana Es Un Maquillaje’ | Cultura | EL PAÍS,” accessed September 2, 2022, https://elpais.com/cultura/2015/02/13/actualidad/1423851530_536670.html.

[16] Abel Sierra Madero, El Cuerpo Nunca Olvida: Trabajo Forzado Hombre Nuevo y Memoria En Cuba (1959-1980) (Rialta Ediciones, 2022).

[17] Conducta Impropia Documental Sobre La Represion al Homosexualismo En Cuba.

[18] “La Jornada: Impulsan Investigación En Cuba Sobre Abusos a Homosexuales En Las UMAP,” accessed August 23, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2011/08/12/mundo/037n1mun.

[19] “La Jornada: Soy El Responsable de La Persecución a Homosexuales Que Hubo En Cuba: Fidel Castro,” accessed August 23, 2022, https://www.jornada.com.mx/2010/08/31/index.php?section=mundo&article=026e1mun.

[20] Ignacio Ramonet, Cien Horas Con Fidel: Conversasiones Con Ignacio Ramonet (La Habana: Oficina de Publicaciones del Consejo de Estado, 2006).

[21] “La Jornada: Soy El Responsable de La Persecución a Homosexuales Que Hubo En Cuba: Fidel Castro.”

[22] “LGTBI: La Revolución de La Comunidad Gay En Cuba | Planeta Futuro | EL PAÍS,” accessed September 4, 2022, https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/05/08/planeta_futuro/1494257202_915266.html.

[23] “Self – LESLIE FEINBERG,” accessed September 2, 2022, https://www.lesliefeinberg.net/self/.

[24] Leslie Feinberg, Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba (New York: World View Forum, 2009), xi.

[25] Feinberg, xiii.

[26] Feinberg, p. 19.

[27] Feinberg, Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba, 21–22.

[28] Feinberg, 22.

[29] “‘La Apertura Cubana Es Un Maquillaje’ | Cultura | EL PAÍS.”

[30] “El Concierto Más Emocionante de Pablo Milanés En La Habana | Cultura | EL PAÍS,” accessed September 2, 2022, https://elpais.com/cultura/2022-06-22/el-concierto-mas-emocionante-de-pablo-milanes-en-la-habana.html.

[31] Ernesto Cardenal, In Cuba (New York: New Directions, 1974), 292–93.

[32] Guerra, Visions of Power in Cuba: Revolution, Redemption, and Resistance, 1959-1971, 254.

[33] Feinberg, Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba, 23–24.

[34] Feinberg, Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba, 23.

[35] “JON HILLSON: 1949-2004 Selected Writings by and about a Cuba Solidarity Activist,” accessed September 3, 2022, http://www.walterlippmann.com/hillson.html.

[36] Jon Hillson, “Sex, Fiction, and Truth: Reinaldo Arenas and the Cuban Revolution,” accessed September 3, 2022, https://nnoc.org/cubasolidarity/aboutcuba/topics/homosexuality/0101hillsonarenas.htm.

[37] “JON HILLSON: 1949-2004 Selected Writings by and about a Cuba Solidarity Activist.”

[38] Ernesto Cardenal, “Entrevista: Los Malos Poetas Es Por Falta de Humanidad,” El Hilo Azul, Winter 2013.

[39] Cardenal, In Cuba.

[40] Cardenal, “Entrevista: Los Malos Poetas Es Por Falta de Humanidad,” 154.

[41] Cardenal, 19.

[42] Cardenal, 20.

[43] Cardenal, 20.

[44] Cardenal, 21.

[45] Cardenal, 22.

[46] Cardenal, 243.

[47] Cardenal, 236.

[48] Cardenal, In Cuba, 79.

[49] Guerra, Visions of Power in Cuba: Revolution, Redemption, and Resistance, 1959-1971, 313.

[50] Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Cuba in the 1970s: Pragmatism and Institutionalization (Albaquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1978), 8–18.

[51] Guerra, Visions of Power in Cuba: Revolution, Redemption, and Resistance, 1959-1971, 290–316.

[52] Kepa Artaraz, Cuba and Western Intellectuals since 1959 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 191.